Call: 708-425-9080

Heat Shields: Materials And Cost Considerations

The following article is actually the pre-print version of a poster presented by Ed Bonnema at the recent CEC-ICMC 2011 conference. The impetus for the paper and poster was the result of a series of conversations with customers whom had expressed further interest in the topic after previous articles that appeared in our July 2010 newsletter entitled “Trends in Thermal Shields: Copper or Aluminum” and our November 2010 newsletter entitled “Heat Shield Design Guidelines”. Ed spoke with more than a dozen people in the 1.5 hour poster presentation and wishes to thank everyone for stopping by and making the time pass so quickly.

Abstract

Heat shields reduce the operating cost of a system by intercepting radiated heat that would otherwise add to the load on the low-temperature stage of the system. While always a consideration, recent fluctuations in the cost of helium have made the use of effective heat shields all the more critical to the cost-effective operation of liquid helium systems. Heat shields come in many forms: they may be completely passive, relying on a low emissivity for effective operation; or they may be actively cooled by helium vapor, an intermediate stage of a refrigerator or by liquid nitrogen. For actively cooled heat shields a high thermal conductivity as well as a low emissivity is desirable. Structural considerations, such as the need to support the cold stage of the system, as well as space limitations, may also factor in to heat shield design. Heat shields have traditionally been fabricated from copper and aluminum, when the highest possible thermal conductivity is required, and to a lesser extent from stainless steel. These materials have very different mechanical properties, are assembled with different fabrication techniques and have very different installed costs. In this paper we examine heat shield design options over a range of conditions and compare the costs of different materials and design options.

Introduction

Heat shields are often thought of primarily as radiation shields; limiting the heat radiated from a warm surface to a cold surface. In practice, a cold mass requires some form of mechanical support and the heat shield may also play an important role in intercepting heat conducted through supports. In principle the need for a heat shield is a matter of economics; reducing the heat load on the coldest surfaces reduces the refrigeration requirements and thereby the operating cost of a system. In practice, the heat shield is often a necessity because unlimited refrigeration at very low temperatures is not available.

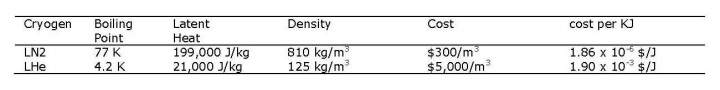

Table 1. Properties and Costs of Refrigerants. The cost for liquid helium is a typical cost for an institution operating a liquefier. This cost will vary with the size and condition of the plant. The cost for liquid helium purchased commercially will be considerably higher at this time. The cost of liquid nitrogen is a current commercial rate for small dewars.

Abstract

Heat shields reduce the operating cost of a system by intercepting radiated heat that would otherwise add to the load on the low-temperature stage of the system. While always a consideration, recent fluctuations in the cost of helium have made the use of effective heat shields all the more critical to the cost-effective operation of liquid helium systems. Heat shields come in many forms: they may be completely passive, relying on a low emissivity for effective operation; or they may be actively cooled by helium vapor, an intermediate stage of a refrigerator or by liquid nitrogen. For actively cooled heat shields a high thermal conductivity as well as a low emissivity is desirable. Structural considerations, such as the need to support the cold stage of the system, as well as space limitations, may also factor in to heat shield design. Heat shields have traditionally been fabricated from copper and aluminum, when the highest possible thermal conductivity is required, and to a lesser extent from stainless steel. These materials have very different mechanical properties, are assembled with different fabrication techniques and have very different installed costs. In this paper we examine heat shield design options over a range of conditions and compare the costs of different materials and design options.

Introduction

Heat shields are often thought of primarily as radiation shields; limiting the heat radiated from a warm surface to a cold surface. In practice, a cold mass requires some form of mechanical support and the heat shield may also play an important role in intercepting heat conducted through supports. In principle the need for a heat shield is a matter of economics; reducing the heat load on the coldest surfaces reduces the refrigeration requirements and thereby the operating cost of a system. In practice, the heat shield is often a necessity because unlimited refrigeration at very low temperatures is not available.

Table 1. Properties and Costs of Refrigerants. The cost for liquid helium is a typical cost for an institution operating a liquefier. This cost will vary with the size and condition of the plant. The cost for liquid helium purchased commercially will be considerably higher at this time. The cost of liquid nitrogen is a current commercial rate for small dewars.

To get an idea for the costs involved, consider the situation we encounter most frequently; a heat shield at 80K, cooled by liquid nitrogen, shielding a vessel containing liquid helium at 4K.

In the absence of an actively cooled heat shield we assume that the 4K surface is surrounded by an MLI blanket which reduces the heat load on the 4K surface to approximately 1 W/m2. (Studies at CERN [1] indicate that the heat flux from a 300K surface to a surface at 77K or at 4K is approximately the same. The value 1 W/m2 is commonly used for engineering purposes.) If this heat flux is absorbed by boiling liquid helium, the cost corresponds to approximately $60,000 per year for each m2 of surface area. The cost of absorbing the same heat by boiling liquid nitrogen is approximately $56. The installation of a liquid nitrogen cooled heat shield, while maintaining proper shielding on the 4K surface, would be expected to reduce the heat flux to ~0.07 W/m2 and the cost of evaporated liquid helium to approximately $4,200 per year for each m2 of surface area. Assume that our 1 m2 of 4K surface area is in the form of a cylinder 0.46 m in diameter and 0.46 m long. If we surround this by a 0.0016 m thick C101 copper heat shield 0.50 m in diameter and 0.50 m long the cost of materials will be approximately $500. For a similar heat shield we recently designed for a customer, the cost of cutting and forming operations, shop labor to install the heat shield, as well as engineering overhead to design it, would bring the total cost of our hypothetical heat shield to approximately $2,000. This heat shield would pay for itself in the first two weeks of operation. We have considered only the radiated heat load. Adding an additional heat load due to conduction through supports would make the economic case for including the heat shield even more compelling.

Materials

Heat shields for terrestrial applications are frequently made of copper. In applications such as space flight or balloon-borne instruments, where weight is a primary concern, aluminum heat shields are favored. While copper and aluminum both have high thermal conductivities, copper has traditionally been favored because of the ease of joining copper to copper and copper to stainless steel. Copper may be joined to copper by welding, brazing (TIG and torch) using BCuP alloys, silver soldering using BAg alloys, and soft soldering. Copper may be joined to stainless steel by silver soldering with BAg alloys. All of these joints provide for good thermal contact. Soldering or brazing stainless steel to copper requires a corrosive flux which must be thoroughly cleaned away from piping after soldering. Some users avoid brazing to stainless steel to avoid the possibility of leaks caused by corrosion induced by flux that was not effectively removed. TIG brazing with BCuP alloys may appear to be an efficient means of joining copper to stainless steel without the use of flux, however we, as well as others in this field, have experienced failures of stainless steel tubing after TIG brazing. Also, the manufacturers of BCuP alloys do not recommend them for use with stainless steel. Joints between copper and stainless steel can also be made with screws or rivets. Copper and stainless steel have similar coefficients of thermal expansion.

Aluminum can be joined to aluminum by welding. Aluminum joints can be brazed; however, the furnace and dip brazing techniques used with aluminum are specialized and not normally employed in shield fabrication. Explosion bonded joints between aluminum and stainless steel are available and are often used to join aluminum to stainless steel piping. Aluminum and stainless steel joints may be joined with fasteners; however, due to their differing rates of thermal expansion, it may be desirable to use spring washers to maintain good contact of these joints.

It is often desirable to join cryogen lines to a heat shield. Aluminum "foot tubing" is available in both P and D profiles for this purpose. The foot may be welded to the heat shield for good thermal contact without the risk of melting through the tube. In small quantities of 75 m, a custom extruded 6061 aluminum tube of this type is expected to cost approximately $25/meter. This is several times the cost of commercial copper tubing of similar dimensions. However, most of this cost is in one-time charges and in longer lengths, the cost of aluminum custom extruded foot tube and copper tube would compare more favorably. The aluminum tube may be joined to stainless steel tube by welding, using explosion bonded bimetallic joints or by using demountable Conflat™ flanges which are available in both aluminum and stainless steel. Stainless steel tubing may also be joined directly to the heat shield using mechanical fasteners. Heat sink compounds such as Apiezon N can be helpful in achieving good thermal contact. Explosion bonded aluminum– stainless steel plates may also be used to join stainless steel tube to an aluminum shell with welded joints which make good thermal contact and have good long-term reliability.

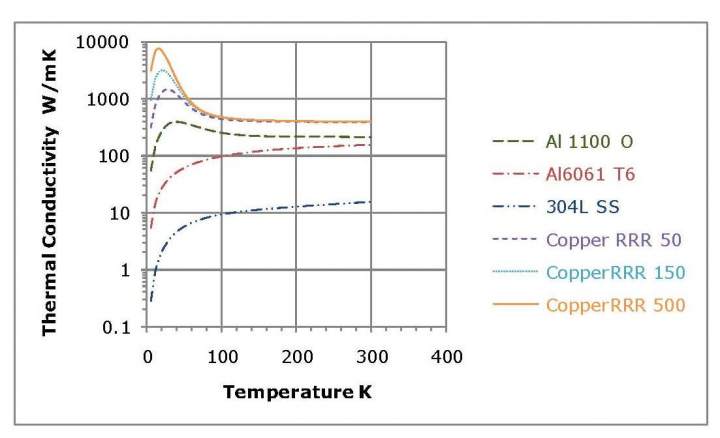

Aluminum and copper are both available in a range of alloys and tempers. The various copper alloys have almost identical thermal conductivities at 300K and similar thermal conductivities at 80K; however, at lower temperatures they diverge sharply. The thermal conductivities of the various aluminum alloys differ considerably at room temperature and the divergence becomes even greater at low temperatures. The thermal conductivities of aluminum and copper alloys as a function of temperature are shown in Figure 1.

In the absence of an actively cooled heat shield we assume that the 4K surface is surrounded by an MLI blanket which reduces the heat load on the 4K surface to approximately 1 W/m2. (Studies at CERN [1] indicate that the heat flux from a 300K surface to a surface at 77K or at 4K is approximately the same. The value 1 W/m2 is commonly used for engineering purposes.) If this heat flux is absorbed by boiling liquid helium, the cost corresponds to approximately $60,000 per year for each m2 of surface area. The cost of absorbing the same heat by boiling liquid nitrogen is approximately $56. The installation of a liquid nitrogen cooled heat shield, while maintaining proper shielding on the 4K surface, would be expected to reduce the heat flux to ~0.07 W/m2 and the cost of evaporated liquid helium to approximately $4,200 per year for each m2 of surface area. Assume that our 1 m2 of 4K surface area is in the form of a cylinder 0.46 m in diameter and 0.46 m long. If we surround this by a 0.0016 m thick C101 copper heat shield 0.50 m in diameter and 0.50 m long the cost of materials will be approximately $500. For a similar heat shield we recently designed for a customer, the cost of cutting and forming operations, shop labor to install the heat shield, as well as engineering overhead to design it, would bring the total cost of our hypothetical heat shield to approximately $2,000. This heat shield would pay for itself in the first two weeks of operation. We have considered only the radiated heat load. Adding an additional heat load due to conduction through supports would make the economic case for including the heat shield even more compelling.

Materials

Heat shields for terrestrial applications are frequently made of copper. In applications such as space flight or balloon-borne instruments, where weight is a primary concern, aluminum heat shields are favored. While copper and aluminum both have high thermal conductivities, copper has traditionally been favored because of the ease of joining copper to copper and copper to stainless steel. Copper may be joined to copper by welding, brazing (TIG and torch) using BCuP alloys, silver soldering using BAg alloys, and soft soldering. Copper may be joined to stainless steel by silver soldering with BAg alloys. All of these joints provide for good thermal contact. Soldering or brazing stainless steel to copper requires a corrosive flux which must be thoroughly cleaned away from piping after soldering. Some users avoid brazing to stainless steel to avoid the possibility of leaks caused by corrosion induced by flux that was not effectively removed. TIG brazing with BCuP alloys may appear to be an efficient means of joining copper to stainless steel without the use of flux, however we, as well as others in this field, have experienced failures of stainless steel tubing after TIG brazing. Also, the manufacturers of BCuP alloys do not recommend them for use with stainless steel. Joints between copper and stainless steel can also be made with screws or rivets. Copper and stainless steel have similar coefficients of thermal expansion.

Aluminum can be joined to aluminum by welding. Aluminum joints can be brazed; however, the furnace and dip brazing techniques used with aluminum are specialized and not normally employed in shield fabrication. Explosion bonded joints between aluminum and stainless steel are available and are often used to join aluminum to stainless steel piping. Aluminum and stainless steel joints may be joined with fasteners; however, due to their differing rates of thermal expansion, it may be desirable to use spring washers to maintain good contact of these joints.

It is often desirable to join cryogen lines to a heat shield. Aluminum "foot tubing" is available in both P and D profiles for this purpose. The foot may be welded to the heat shield for good thermal contact without the risk of melting through the tube. In small quantities of 75 m, a custom extruded 6061 aluminum tube of this type is expected to cost approximately $25/meter. This is several times the cost of commercial copper tubing of similar dimensions. However, most of this cost is in one-time charges and in longer lengths, the cost of aluminum custom extruded foot tube and copper tube would compare more favorably. The aluminum tube may be joined to stainless steel tube by welding, using explosion bonded bimetallic joints or by using demountable Conflat™ flanges which are available in both aluminum and stainless steel. Stainless steel tubing may also be joined directly to the heat shield using mechanical fasteners. Heat sink compounds such as Apiezon N can be helpful in achieving good thermal contact. Explosion bonded aluminum– stainless steel plates may also be used to join stainless steel tube to an aluminum shell with welded joints which make good thermal contact and have good long-term reliability.

Aluminum and copper are both available in a range of alloys and tempers. The various copper alloys have almost identical thermal conductivities at 300K and similar thermal conductivities at 80K; however, at lower temperatures they diverge sharply. The thermal conductivities of the various aluminum alloys differ considerably at room temperature and the divergence becomes even greater at low temperatures. The thermal conductivities of aluminum and copper alloys as a function of temperature are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Thermal conductivities of copper and aluminum alloys as a function of temperature. The data plotted is from reference [3].

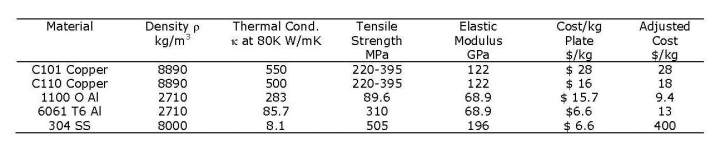

Table 2. Properties of potential heat shield materials. Mechanical properties are from Reference [2]. Thermal properties are from Reference [3] with C101 copper corresponding or a residual resistance ratio (RRR) of 300 and C110 copper corresponding to an RRR of 50.

Table 2. Properties of potential heat shield materials. Mechanical properties are from Reference [2]. Thermal properties are from Reference [3] with C101 copper corresponding or a residual resistance ratio (RRR) of 300 and C110 copper corresponding to an RRR of 50.

Material Cost Comparison

We will compare materials for a heat shield operating at 80K. In Table 2 we compare the properties and costs of some candidate materials for heat shield fabrication. Material prices will vary according to the form and thickness of the material, however, the price per unit weight will vary within a reasonably narrow range and gives us a basis on which to compare materials. The prices used here are an average for thin plate or sheet form. The 1100-O alloy of aluminum is not as widely available as 6061-T6 and its price varies widely between different suppliers. The thicknesses available for 1100-O aluminum are limited. At this writing material prices are fluctuating.

The thermal conductivity of a given alloy will depend on its temper. This is most pronounced in the high purity alloys such as 1100-O and C101. The lattice defects introduced by cold working make these materials harder while at the same time reducing their thermal conductivity.

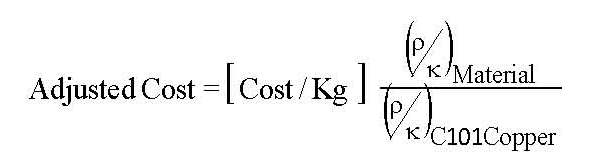

If we wish to minimize the cost of a heat shield then we will choose the material thickness to be the minimum value required to stay within the allowed temperature variation over the heat shield. The thickness of the shield, and its cost, will scale inversely with the thermal conductivity of the material. Since we have the cost per unit weight, then we must scale the cost in proportion to the density. In the Adjusted Cost column of Table 2 the material costs per unit weight are scaled in proportion to the density divided by the thermal conductivity at 80K and normalized to C101 copper.

We will compare materials for a heat shield operating at 80K. In Table 2 we compare the properties and costs of some candidate materials for heat shield fabrication. Material prices will vary according to the form and thickness of the material, however, the price per unit weight will vary within a reasonably narrow range and gives us a basis on which to compare materials. The prices used here are an average for thin plate or sheet form. The 1100-O alloy of aluminum is not as widely available as 6061-T6 and its price varies widely between different suppliers. The thicknesses available for 1100-O aluminum are limited. At this writing material prices are fluctuating.

The thermal conductivity of a given alloy will depend on its temper. This is most pronounced in the high purity alloys such as 1100-O and C101. The lattice defects introduced by cold working make these materials harder while at the same time reducing their thermal conductivity.

If we wish to minimize the cost of a heat shield then we will choose the material thickness to be the minimum value required to stay within the allowed temperature variation over the heat shield. The thickness of the shield, and its cost, will scale inversely with the thermal conductivity of the material. Since we have the cost per unit weight, then we must scale the cost in proportion to the density. In the Adjusted Cost column of Table 2 the material costs per unit weight are scaled in proportion to the density divided by the thermal conductivity at 80K and normalized to C101 copper.

The values given in Table 2 suggest that there is little justification for specifying C101 copper for heat shields operating at 80K. This conclusion may not apply at lower temperatures where the spread in thermal conductivities of the two alloys is much larger.

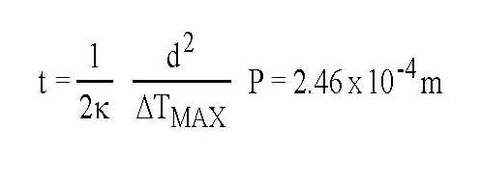

The values given in Table 2 also suggest that aluminum will have the cost advantage as the material for heat shield fabrication. This conclusion is based on a comparison of heat shields having the same thermal properties. If the mechanical properties of copper force the thickness of the copper heat shield to be greater than that required by thermal considerations, then the cost advantage of aluminum is magnified. For example, suppose that we have a heat shield which is a long cylinder 1 m in diameter. We assume that the heat shield is heat sunk to and supported by a rigid tube at 80K running along its length. The heat shield is subjected to a uniform heat load of P = 1 W/m2 and we require that the temperature rise not exceed 10K. The peak temperature will occur half way around the circumference at distance d = 1.57 m from the cooling line. The required thickness of a C110 copper heat shield would be:

The values given in Table 2 also suggest that aluminum will have the cost advantage as the material for heat shield fabrication. This conclusion is based on a comparison of heat shields having the same thermal properties. If the mechanical properties of copper force the thickness of the copper heat shield to be greater than that required by thermal considerations, then the cost advantage of aluminum is magnified. For example, suppose that we have a heat shield which is a long cylinder 1 m in diameter. We assume that the heat shield is heat sunk to and supported by a rigid tube at 80K running along its length. The heat shield is subjected to a uniform heat load of P = 1 W/m2 and we require that the temperature rise not exceed 10K. The peak temperature will occur half way around the circumference at distance d = 1.57 m from the cooling line. The required thickness of a C110 copper heat shield would be:

The cost of material for a shell of this thickness would be $110/m, however, this cylinder would deform significantly under its own weight, requiring either a thicker shell or a support structure. In either case the cost of the copper shell would increase. The corresponding thickness of a 6061 aluminum heat shield under the same conditions would be 1.4 x 10-3 m, offering a considerably more rigid structure. The cost of material for the 6061 aluminum heat shield would be $78.6/m. The cost of material for a copper heat shield of the same 1.4 x 10-3 m thickness as the 6061 aluminum shield would cost $625/m.

Stainless steel fares quite poorly in terms of cost effectiveness. There will still be applications in which availability and ease of fabrication override cost concerns, particularly for small cryostats.

Other Aluminum Alloys

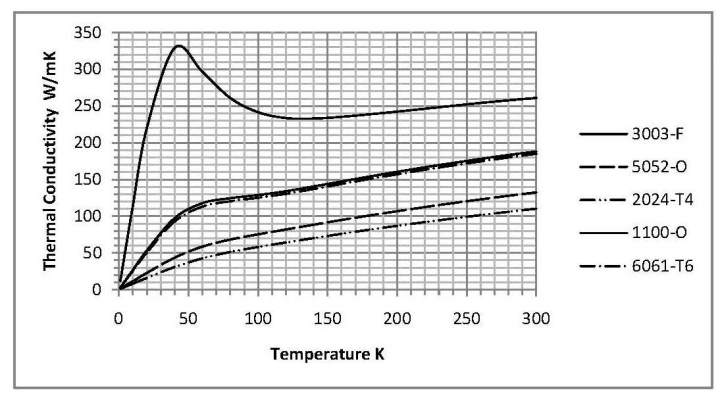

The alloy 1100-O is commercially pure aluminum (99.0%) and 6061 aluminum is relatively pure, containing only 1% magnesium and 0.6% silicon. Some other common alloys available in sheet form include 3003, 5052, 2024. The thermal conductivities of these alloys as a function of temperature are given in Figure 2.

The 3003 alloy is also relatively pure aluminum, containing 1.2% manganese, and its thermal conductivity is similar to that of the 6061 alloy. As expected, the less pure alloys have a lower thermal conductivity; however, they may give the designer greater flexibility in terms of the available thickness and sheet dimensions.

Stainless steel fares quite poorly in terms of cost effectiveness. There will still be applications in which availability and ease of fabrication override cost concerns, particularly for small cryostats.

Other Aluminum Alloys

The alloy 1100-O is commercially pure aluminum (99.0%) and 6061 aluminum is relatively pure, containing only 1% magnesium and 0.6% silicon. Some other common alloys available in sheet form include 3003, 5052, 2024. The thermal conductivities of these alloys as a function of temperature are given in Figure 2.

The 3003 alloy is also relatively pure aluminum, containing 1.2% manganese, and its thermal conductivity is similar to that of the 6061 alloy. As expected, the less pure alloys have a lower thermal conductivity; however, they may give the designer greater flexibility in terms of the available thickness and sheet dimensions.

Figure 2. Thermal conductivities of several aluminum alloys. Generated using parameters from reference [4].

Potential Pitfalls

Welding aluminum is generally regarded as more difficult than welding stainless steel, and the high temperatures required can cause a thin structure such as would be used for a heat shield to deform.

In very low temperature applications the transition of aluminum to the superconducting state will reduce the thermal conductivity and may cause some unexpected effects. The transition temperature for pure aluminum is 1.2K. This situation should only be encountered when a pumped 4He bath is used to heat sink shields structures. This would be the case in dilution refrigerators and possibly in 3He evaporation cryostats.

Conclusions

For heat shields operating at 80K, aluminum has a cost advantage over copper as the material of construction, assuming that labor costs for the two materials are the same. Highly pure alloys such as 1100-O aluminum have superior thermal properties, but that is more than offset by its higher price. The cost advantage of 6061 aluminum over C101 copper is more than a factor of two; however, the factor drops to 1.4 if we compare 6061 aluminum with the less expensive C110 copper alloy.

References

1. Mazzone, L., Ratcliffe, G., Rieubland, J.M. and Vandoni, G. “Measurements of Multi-Layer Insulation at High Boundary Temperature Using a Simple, Non-Calorimetric Method”, Proceedings of the 19th International Cryogenic Engineering Conference, Narosa, New Delhi, India (2003).

2. MatWeb, http://www.matweb.com/, date accessed, May 3, 2011.

3. National Institute for Standards and Technology, Cryogenic Materials Group

http://cryogenics.nist.gov/MPropsMAY/material%20properties.htm, date accessed July 8, 2010.

4. Woodcraft, Adam L. “Predicting the thermal conductivity of aluminum alloys in the cryogenic to room temperature range”, Cryogenics 45(6), pp.421-431 (2005).

Potential Pitfalls

Welding aluminum is generally regarded as more difficult than welding stainless steel, and the high temperatures required can cause a thin structure such as would be used for a heat shield to deform.

In very low temperature applications the transition of aluminum to the superconducting state will reduce the thermal conductivity and may cause some unexpected effects. The transition temperature for pure aluminum is 1.2K. This situation should only be encountered when a pumped 4He bath is used to heat sink shields structures. This would be the case in dilution refrigerators and possibly in 3He evaporation cryostats.

Conclusions

For heat shields operating at 80K, aluminum has a cost advantage over copper as the material of construction, assuming that labor costs for the two materials are the same. Highly pure alloys such as 1100-O aluminum have superior thermal properties, but that is more than offset by its higher price. The cost advantage of 6061 aluminum over C101 copper is more than a factor of two; however, the factor drops to 1.4 if we compare 6061 aluminum with the less expensive C110 copper alloy.

References

1. Mazzone, L., Ratcliffe, G., Rieubland, J.M. and Vandoni, G. “Measurements of Multi-Layer Insulation at High Boundary Temperature Using a Simple, Non-Calorimetric Method”, Proceedings of the 19th International Cryogenic Engineering Conference, Narosa, New Delhi, India (2003).

2. MatWeb, http://www.matweb.com/, date accessed, May 3, 2011.

3. National Institute for Standards and Technology, Cryogenic Materials Group

http://cryogenics.nist.gov/MPropsMAY/material%20properties.htm, date accessed July 8, 2010.

4. Woodcraft, Adam L. “Predicting the thermal conductivity of aluminum alloys in the cryogenic to room temperature range”, Cryogenics 45(6), pp.421-431 (2005).