Call: 708-425-9080

Vacuum Compatible Metals and Alloys

Our January 2012 newsletter featured an article discussing the use of silicon bronze nuts with stainless steel bolts to avoid galling. The application we had in mind was bolting up flanges external to a vacuum chamber. However, this prompted one reader to ask whether the high zinc content of silicon bronze might make these fasteners unsuitable for use inside a vacuum chamber. Zinc and cadmium are two common materials which are often avoided in high vacuum systems due to their high vapor pressures.

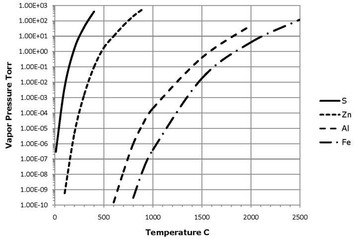

The vapor pressures of most familiar metals are well below 1 x 10-6 Torr at room temperature. The vapor pressure of a material rises sharply with temperature. An extensive compilation of vapor pressures of the elements as a function of temperature was undertaken by Richard Honig and his colleagues at RCA in the early 1960’s. This data is still in use today.

High and ultrahigh vacuum vessels often undergo bake-out procedures at temperatures of 200°C or 400°C. At 200°C the vapor pressure of zinc is approximately 5 x 10-6 Torr while that of cadmium is 3 x 10-4 Torr. At 400°C these rise to roughly 0.1 Torr and 1 Torr respectively. Small carbon steel fasteners are frequently cadmium plated. Zinc is found in brass (4% to 12%), silicon bronze (1.5% (Alloy C651) to 34% (Alloy C879)) and 7000 series aluminum (typically ~5%). Heating these materials in a vacuum can cause cadmium or zinc to be evaporated. While this could limit the system pressure, the greater concern is often that cadmium or zinc will condense on cooler parts of the system, possibly contaminating sensitive items such as optical surfaces.

Brass parts can be nickel plated to reduce the evaporation of zinc.

Two common elements which are solid at room temperature but which also have relatively high vapor pressures are sulfur and phosphorus. The vapor pressure of sulfur is approximately 1 x 10-6 Torr at 20°C and approaches 1 x 10-2 Torr at 100°C. Free machining 303 stainless steel contains 0.15% (minimum) sulfur and is generally avoided in high vacuum work for that reason. Cutting oils which contain sulfur are also avoided in the fabrication of high vacuum equipment. The vapor pressure of elemental phosphorus is quite high; however, phosphorus is highly reactive and elemental phosphorus is not likely to be encountered in high vacuum work. Phosphorus is the form of copper phosphide that is found in phosphor bronze alloys in brazing alloys. These materials must be heated to very high temperatures (as in brazing) to release elemental phosphorus. Some practitioners avoid alloys containing phosphorus as a precaution. Phosphor bronze alloys contain zinc at levels ranging from 0.2% (C521) to 3% (C544).

The vapor pressures of most familiar metals are well below 1 x 10-6 Torr at room temperature. The vapor pressure of a material rises sharply with temperature. An extensive compilation of vapor pressures of the elements as a function of temperature was undertaken by Richard Honig and his colleagues at RCA in the early 1960’s. This data is still in use today.

High and ultrahigh vacuum vessels often undergo bake-out procedures at temperatures of 200°C or 400°C. At 200°C the vapor pressure of zinc is approximately 5 x 10-6 Torr while that of cadmium is 3 x 10-4 Torr. At 400°C these rise to roughly 0.1 Torr and 1 Torr respectively. Small carbon steel fasteners are frequently cadmium plated. Zinc is found in brass (4% to 12%), silicon bronze (1.5% (Alloy C651) to 34% (Alloy C879)) and 7000 series aluminum (typically ~5%). Heating these materials in a vacuum can cause cadmium or zinc to be evaporated. While this could limit the system pressure, the greater concern is often that cadmium or zinc will condense on cooler parts of the system, possibly contaminating sensitive items such as optical surfaces.

Brass parts can be nickel plated to reduce the evaporation of zinc.

Two common elements which are solid at room temperature but which also have relatively high vapor pressures are sulfur and phosphorus. The vapor pressure of sulfur is approximately 1 x 10-6 Torr at 20°C and approaches 1 x 10-2 Torr at 100°C. Free machining 303 stainless steel contains 0.15% (minimum) sulfur and is generally avoided in high vacuum work for that reason. Cutting oils which contain sulfur are also avoided in the fabrication of high vacuum equipment. The vapor pressure of elemental phosphorus is quite high; however, phosphorus is highly reactive and elemental phosphorus is not likely to be encountered in high vacuum work. Phosphorus is the form of copper phosphide that is found in phosphor bronze alloys in brazing alloys. These materials must be heated to very high temperatures (as in brazing) to release elemental phosphorus. Some practitioners avoid alloys containing phosphorus as a precaution. Phosphor bronze alloys contain zinc at levels ranging from 0.2% (C521) to 3% (C544).

Selenium also has a relatively high vapor pressure (between zinc and sulfur, approaching 1 x 10-6 Torr at 100°C). It is only likely to be encountered in free machining 303 Se stainless steel.

Lead is avoided in some applications. The vapor pressure of lead is considerably lower than that of materials such as sulfur and zinc. Lead must be heated to over 400°C for the vapor pressure to reach 1 x 10-6 Torr. While lead is unlikely to be the material of construction for vacuum equipment, it may be used as shielding or collimators inside a vacuum chamber and could also be introduced as solder.

The vapor pressure, as a function of temperature, serves as a guide to selecting materials for high vacuum applications and in determining what materials are suitable for service at elevated temperatures. There are often no perfect choices. Both 316 and 304 stainless steels, the most popular materials for high vacuum fabrication, contain 0.03% sulfur. The aluminum alloy 6061, also widely used, contains 0.25% zinc.

The vapor pressure of a substance is the pressure of the vapor over a solid or a liquid when the vapor and the source are in thermal equilibrium, meaning that they must be at the same temperature. In systems at very low pressure, the mean free path is long and a vapor molecule may make many collisions with the walls of the chamber and relatively few collisions with other vapor molecules or with the surface from which it evaporated. If the walls of the chamber are at a very different temperature than the evaporation source then the vapor may be at a very different temperature from the evaporation source. The use of vapor pressures under these circumstances must be done with some care.

Considerable thought on the issues of materials compatible with high vacuum has gone into the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO). See, for example LIGO Vacuum Compatible Materials List.

Responding to our reader’s original question, “Since C651 can consist of up to 1.5% zinc would that make it unsuitable for bakeout under UHV?” Our opinion is that silicone bronze fasteners would be unsuitable in a system requiring bakeout. They would, however, be perfectly suitable for vacuum systems that do not see elevated temperatures, one example being in the insulation vacuum of a cryostat.

Opening a vacuum chamber to find the interior of the chamber and its contents coated with a fine layer of zinc can come as a surprise. At Meyer Tool we strive to help our customers avoid surprises like this and thereby achieve the lowest total cost of ownership.

Lead is avoided in some applications. The vapor pressure of lead is considerably lower than that of materials such as sulfur and zinc. Lead must be heated to over 400°C for the vapor pressure to reach 1 x 10-6 Torr. While lead is unlikely to be the material of construction for vacuum equipment, it may be used as shielding or collimators inside a vacuum chamber and could also be introduced as solder.

The vapor pressure, as a function of temperature, serves as a guide to selecting materials for high vacuum applications and in determining what materials are suitable for service at elevated temperatures. There are often no perfect choices. Both 316 and 304 stainless steels, the most popular materials for high vacuum fabrication, contain 0.03% sulfur. The aluminum alloy 6061, also widely used, contains 0.25% zinc.

The vapor pressure of a substance is the pressure of the vapor over a solid or a liquid when the vapor and the source are in thermal equilibrium, meaning that they must be at the same temperature. In systems at very low pressure, the mean free path is long and a vapor molecule may make many collisions with the walls of the chamber and relatively few collisions with other vapor molecules or with the surface from which it evaporated. If the walls of the chamber are at a very different temperature than the evaporation source then the vapor may be at a very different temperature from the evaporation source. The use of vapor pressures under these circumstances must be done with some care.

Considerable thought on the issues of materials compatible with high vacuum has gone into the Laser Interferometer Gravitational Wave Observatory (LIGO). See, for example LIGO Vacuum Compatible Materials List.

Responding to our reader’s original question, “Since C651 can consist of up to 1.5% zinc would that make it unsuitable for bakeout under UHV?” Our opinion is that silicone bronze fasteners would be unsuitable in a system requiring bakeout. They would, however, be perfectly suitable for vacuum systems that do not see elevated temperatures, one example being in the insulation vacuum of a cryostat.

Opening a vacuum chamber to find the interior of the chamber and its contents coated with a fine layer of zinc can come as a surprise. At Meyer Tool we strive to help our customers avoid surprises like this and thereby achieve the lowest total cost of ownership.